Everything I Read | June 2025

who would have thought that starting a new business would be so much work?

June has been… a lot. Between the launch of Allurial and my dad’s wedding in France, suffice it to say that sleep deprivation and heightened anxiety have been the name of the game this month. Earlier in June, after finally getting back into journaling, I re-read entries from the beginning of the year. The difference is stark. Back in January and February, my main complaint was my skyrocketing screen time. Today, it hovers at the 3-hour mark, and I’m genuinely happy with my social media usage (thanks in no small part to the Jomo App). I was bored and purposeless with a lackluster job, which had partially prompted the start of this Substack in October. Since March, I have been so fulfilled and excited by my work. I used to dread the two or three days I was forced to go into the Amex Tower, whereas I now genuinely look forward to being in the office 5 days a week. This comparison isn’t to say everything is rosy and perfect now; clearly, I have been very stressed out. But I would much rather that than the abysmal sense of aimlessness I felt for the last two years or so.

Anyway, enough yapping. I didn’t have much time to read this month, because… well… see above. But I read a couple of things, so let’s get into it!

As always, if you’re new and want to read past issues, here’s What I Read | May 2025, April 2025, March 2025, February 2025, January 2025, December 2024, November 2024, and October 2024.

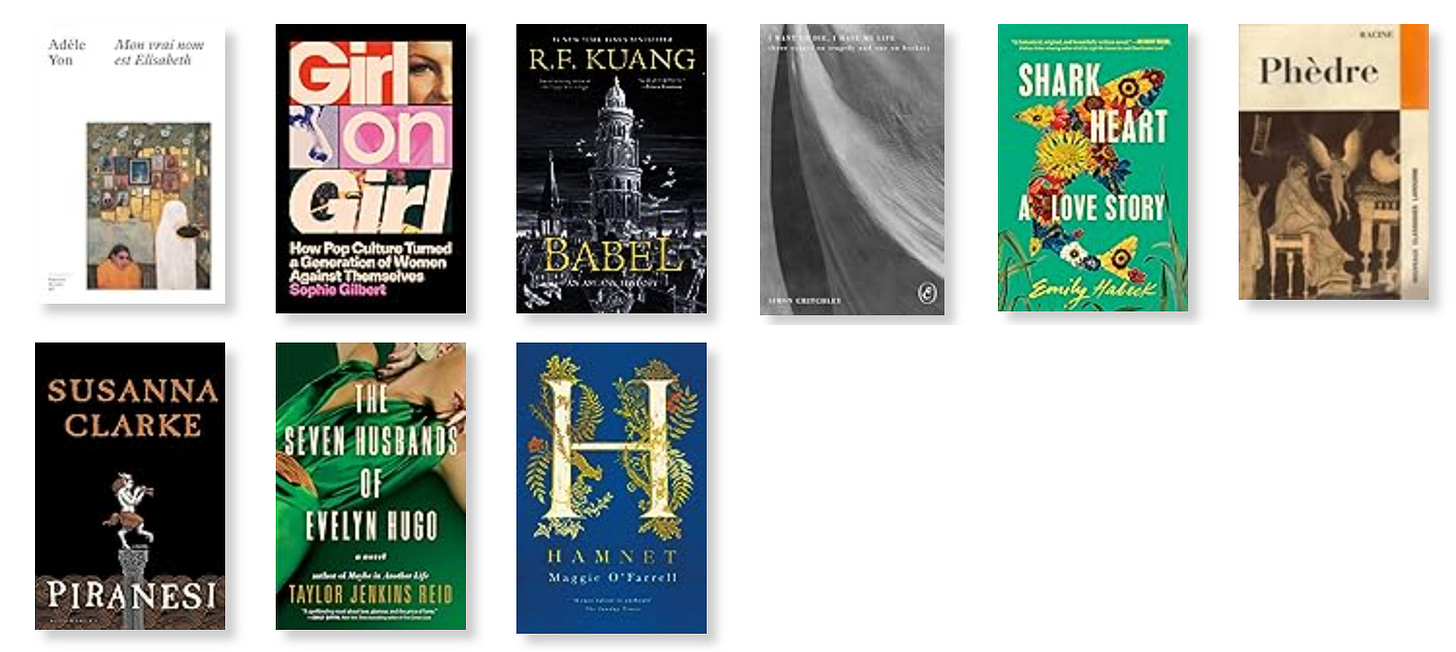

The first book I finished in June, which I teased at the end of last month’s post, was Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell. I picked up a second-hand copy in Colorado, determined to read something Shakespeare-related after DNFing Henry Henry last month. Unfortunately, I think I should just stay away from those, as Hamnet, too, was a slug to get through.

Hamnet follows the fictionalized story of Anne Hathaway, William Shakespeare’s wife, back in their hometown of Stratford in the British countryside. We meet her and William, though he is confusingly never named, as young adults falling in love. She is the eccentric daughter of a well-off farmer; he is a gifted but bored Latin tutor. In Hamnet, and perhaps in real life, Anne pushes William to go to London to escape their stifling family life and his difficult and abusive father. Anne has three children: a first daughter, Susanna, followed by two twins, Hamnet and Judith. In real life, Hamnet died in 1956 and inspired Shakespeare’s famous play Hamlet. In Hamnet, O’Farell focuses on Anne’s dealing with the loss of her son, and in a way, the loss of her husband to London and playwrighting. Ultimately, Hamnet just read like a bizarre fanfic about Shakespeare’s wife and children.

The premise isn’t bad by any means, but I disliked reading Hamnet, in part because of O’Farell’s writing: repetitive, never-ending, comma-filled sentences that are probably meant to be stylistically impressive, but are just long and annoying. As for the plot, there is none. Barely anything happens throughout the novel, and when something does, I found I did not care, because the characters were so incredibly bland and boring.

As I mentioned above, Hamnet was a slog to get through. It took me over three days to move past the first 30 pages. Honestly, had I not just DNF’d Henry Henry, I probably would have also DNF’d Hamnet too.

Next up, I picked up what I assumed would be a quick and fun palate cleanser: The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo by Taylor Jenkins Reid. I was right on the money because this novel was entertaining, fast-paced, and highly addictive. My only real qualm with this book is that it was poorly written.

The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo focuses on the life of Evelyn Hugo, a famous Hollywood actress known for her looks and seven husbands. Towards the end of her life and for no apparent reason, Hugo asks Monique Grant, a young reporter, to write a tell-all about her life. Monique is confused by the ask, but of course agrees to it. The novel follows this interview process, with full chapters focusing on Evelyn’s life and each of her husbands. There is a very obvious plot twist that connects Evelyn with Monique, but I will not spoil it. Both Evelyn and Monique are strong characters, with obvious qualities and flaws that make them feel both accessible and touching. Unlike with Hamnet, I cared about all the characters here, and definitely shed a tear or two.

Honestly, I don’t have too much to say about this book. It’s a fun read, and would be a great way to get anyone out of a reading slump.

Next up, I picked up Piranesi by Susanna Clarke, which had been on my TBR for the longest time (thanks, Jack Edwards). Piranesi is a strange but lovely fantasy novel whose pages I could have stayed in forever.

Piranesi is the diary of an eponymous narrator who lives, admires, and researches the wet and windswept Halls of a strange and flooded House. These Halls are filled with Statues, birds, seaweed, and more. Piranesi writes about the statues, the tides that come in and out to flood the House, the albatros couple and their young chick, the thirteen skeletons he cares for, and his bi-weekly meetings with The Other, another inhabitant of the House. Unlike our narrator, The Other thinks the House harbors the secret to the universe, and wants Piranesi to help him uncover it. Things start to unravel when The Other warns Piranesi of a dangerous person who will come to the House and make Piranesi go crazy if he so much as talks to him. Of course, that person comes and manages to get in touch with Piranesi, who starts to uncover more and more things about a past he did not know he had. I can’t go into much more detail about the plot without spoiling everything, and I recommend going into Piranesi as blind as possible. It will not make any sense until it does, but even then, making sense is not the point of Piranesi.

Despite a bizarre and somewhat stressful plot, I found reading Piranesi to be a very calming and soothing experience, likely because of Clarke’s beautiful and intricate world and thoughtful characters.

I know Piranesi was uber-successful, and while I of course personally loved it, I’m surprised that it appealed to so many. The form and plot are pretty experimental, especially for a fantasy novel, and considering how little sense it made for around three-quarters of the book, I am surprised so many people stuck with it. But again, I am glad they did because it is a near-perfect little book!

After so much fiction, I decided I would switch it up with I Want to Die, I Hate My Life: Three Essays on Tragedy and One on Beckett by Simon Critchley. I can’t lie, I was heavily drawn in by the alluring title.

This little collection comprises four essays: the first on Jean Racine’s Phaedra, the second on the women in Henry Ibsen’s plays, the third on Shakespeare, and the fourth on Samuel Beckett, specifically as a screenwriter.

All four were terrific investigations into their subject matters, with many interesting tie-ins to philosophy. The first essay, on Phaedra, was my favorite, likely because I re-read Phèdre beforehand in preparation, and so got a lot out of Critchley’s analysis of it. The essay on Ibsen was thought-provoking as it focused on Ibsen’s historical women characters, but having read only two of his plays, some of it went over my head. I found the one on Shakespeare to lack a lot of depth, and think it could have been omitted from the collection (what is it with me and Shakespeare lately?!). Finally, the fourth essay, on Beckett, was very interesting and delved into many concepts of cinema that I was not familiar with (as I am not a cinephile). I also finished the essay inspired to read some more Beckett, who is, fun fact, one of the key subjects of my International Baccalaureate Thesis on the theatre of the absurd.

As I mentioned above, picking up Critchley’s collection inspired a re-reading of Racine’s most well-known and well-loved play, Phèdre (or Phaedra in English). Phèdre is such a gorgeous, dramatic play, and if you haven’t read it, I urge you to (it’s part of the standard educational curriculum in the French system). Racine is the most famous “classical” French playwright of the 17th century, and his poetry is pure and harmonious in a way that remains unparalleled. Every other stanza, I would stop to think: “How is it even possible to write this beautifully?”.

In Greek mythology, Phaedra is the daughter of King Minos and Queen Pasiphaë of Crete, step-sister to the Minotaur, and sister to Ariadne, herself famous for helping Theseus defeat the Minotaur. Following Theseus’ abandonment of Ariadne on the island of Naxos, for reasons more or less understood, Theseus has a child, Hippolytus, with the Amazon queen Hippolyta. Later on (again, reasons more or less clear), Theseus marries Phaedra, and they have two children, Demophon and Acamas (though they do not matter here). [SPOILERS AHEAD] In Phèdre, Phaedra becomes infatuated with her adult step-son, Hippolytus, and confesses her love to him when Theseus is rumored to be dead. Theseus returns, finds his wife and his son acting incredibly weird (obviously). Phaedra accuses Hippolytus of having attempted to rape her, and Theseus banishes his son from the city. Hippolytus perishes in an awful way, dragged for miles by his chariot after defeating a monster sent by Neptune, God of the Sea. Phaedra finally confesses the truth to Theseus, right after taking some poison, and dies too.

Phèdre and Phaedra herself are dramatic to say the least, with the eponymous character in a constant state of heartbroken despair. She is, of course, in an impossible situation, knows it, and suffers ever more for it. She cannot do anything about her impossible love, and it leaves her in a state of perpetual agony. Even more tragically, the death she so desperately longs for is not possible: her father, Minos, is one of the guardians of Hell, and her grandfather is literally the sun God Helios. Her love, her suffering, and her humiliation will never end, even in death. And for that reason, folks, Phaedra is a perfect tragedy. But for real, if you are interested, read the play and then read Critchley’s analysis.

And just for fun, here is one of the most famous quotes in French literature, courtesy of our sick heroine:

Je le vis, je rougis, je pâlis à sa vue ;

Un trouble s’éleva dans mon âme éperdue ;

Mes yeux ne voyaient plus, je ne pouvais parler ;

Je sentis tout mon corps et transir et brûler ;

Next up, I read Shark Heart by Emily Habeck, which came highly recommended from the Book of the Month team.

Shark Heart follows the first year of marriage of Lewis and Wren, two very different, but very in love, people. A few weeks after their wedding, Lewis starts to notice strange things on his body: his nose flattens, he is always thirsty, and he develops a patch of gray skin on his lower back. Reluctantly, he goes to his doctor, who diagnoses him with a rare mutation: he is turning into a great white shark. Over the next year, Lewis slowly morphs into this predatory creature, and Wren does all she can to help and support him throughout his transition. Lewis, a failed actor turned high school theatre teacher, fights his diagnosis, convinced there is more for him to do in his one human life. But ultimately, Lewis must be released to the ocean, and he and Wren say their heart-wrenching goodbyes. The second part of the novel follows Lewis as he roams the Earth’s waters, at times alone and depressed, at other times with another human-turned-great-white-shark. We also follow Wren as she heals from the loss of her husband, and the trauma of her childhood and early adulthood it brings up for her.

Shark Heart is, clearly, a very weird novel. But it is so beautiful and moving, and for some reason, someone turning into a shark really got my waterworks going. The writing was lovely, simple, and worked well with the story and the dual focus on Lewis and Wren. The form was interesting, too, with portions written out like plays or like short poetic paragraphs, making for an engaging and novel reading experience.

As long as you don’t mind a little bit of magical realism, I think this book is worth a try, and I’m honestly shocked it didn’t get more hype from the bookish community!

For my trip to France, I wanted a Big Boy book to entertain me across two long transatlantic flights, so I grabbed Babel by R. F. Kuang. Since it’s so popular and I have been enjoying my forays into fantasy lately, I really thought I would like it. trying to Spoiler alert: I really did not.

Babel follows Robin Swift (he gave himself this name, aged 12 or so), as he is taken from Canton following his mother’s death to study languages in London under the care of a mysterious Professor Lovell. Once he reaches 18, Robin Swift enrolls at Oxford’s prestigious Royal Institute of Translation, also known as Babel. Once at Oxford, Robin meets the other three members of his cohort, and the four of them quickly become inseparable, bonded by the intensity of their studies, as well as their love of each other and Oxford (or so we are told by R. F. Kuang). Robin also makes a strange new acquaintance (no spoilers!), who lures him to help fight imperialism one small heist at a time as a pawn for the secretive Hermes Society.

The fantasy system in Babel is a strange one, at best. Somehow, silver bars engraved with pairs of translated words can be imbued with special magical powers, such as making ships stronger and faster, cleaning water, healing the sick, and much, much more. Babel and its scholars essentially support the smooth operations of the entire British Empire. The catch? The classical languages aren’t really cutting it anymore, and translations have to come from native “exotic” speakers, like Robin and his cohort. Sounds unfair? It is, and soon enough, Robin, his friends, and the Hermes Society are in cahoots to stop British Imperialism at any cost.

Again, I really wanted to love Babel, but there were so many things I struggled with.

Firstly, as mentioned above, I thought the magic system and its focus on translation were quite odd. While some of the discussions on language were interesting, those portions often felt like R. F. Kuang showing off. If you want to read a really good book about language and learning Ancient Latin, Greek, and Mandarin, I cannot recommend Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai enough.

The second issue I had with Babel is more of a personal preference, but I find I don’t like fantasy that reads like historical fiction, and which actually actively makes use of real facts. If I wanted to learn about the British Empire, I would read about the British Empire. If I wanted to read fantasy, I would read fantasy. I’m not sure why the two should ever mix, especially when it makes it so difficult to parse through fact and fiction.

Additionally, the characters were unbelievably flat and uninteresting. R. F. Kuang turned each one of her characters into a Super Archetype made up solely of stereotypes. It was impossible to care about any of them. Even when some of them literally died, I didn’t care, because R. F. Kuang does nothing to make you care. For better dark academia novels with interesting (though unlikeable) characters, look no further than The Dark History by Donna Tartt.

Generally, I found the story in Babel, like the characters, to be lackluster. I was bored from the start, and bored throughout the novel, except the last hundred or so pages. As I said, I had two long flights to read this during; otherwise, I’m pretty sure it would have taken me much longer to finish, or I might have just never finished it.

I know people love R. F. Kuang, and since she is herself a scholar, I expected the writing to be solid. It’s not bad by any means, but I also didn’t find it worth raving about at all. It was often too scholarly and pretentious. Additionally, I don’t think anyone ever told her about the “show, don’t tell” rule. We were constantly told things happened, such as the characters’ friendship with each other, but they rarely showed their friendship and closeness in action.

My last point of contention for this book (sorry) was the footnotes. I hated them. I truly, truly hated them. I’ll be honest, I don’t like footnotes that are part of the story, even David Foster Wallace’s. But these footnotes were next-level annoying. Firstly, we don’t know who they are from. They don’t sound like they are from the narrator of the novel, because if that were the case, most of them could have just been folded into the novel itself. Second, they are often just Kuang beating her readers over the head with things that are incredibly obvious, like, uh… Imperialism is bad. Or… White people are always lying and evil. Which is literally the entire point of the novel, so I’m not sure why she thought anyone even remotely literate wouldn’t be able to get this. I’m literally getting riled up just thinking about the footnotes, honestly.

Look, if you’re a fan of fantasy that draws heavily on history, don’t mind a stupid magic system or flat characters, maybe Babel will do the trick for you. It certainly seems to have been a hit amongst thousands of people. I just don’t understand why.

Please fight me in the comments if you disagree.

Throughout the month of June, I listened to the audiobook for Girl on Girl: How Pop Culture Turned a Generation of Women Against Themselves by Sophie Gilbert.

Girl on Girl takes a very detailed look at the treatment of women in popular culture from the early 1980s to today. I do think Girl on Girl achieved its goal, and the premise was interesting, but I personally got pretty tired of reading about all the different ways in which women and women’s bodies have been objectified, humiliated, and commodified over the last forty years. Not because I don’t think it’s true or important, but because I didn’t think the book added anything new to what I already knew and internalized. I wish Gilbert had done more critical thinking and writing, and less listing out.

If you’re (somehow) new to misogyny or basic feminist theory, Girl on Girl might be worthwhile for you, but if you aren’t, I would focus on better feminist literature (should I make a list…)?

The last book I read in June was Mon vrai nom est Elizabeth by Adèle Yon, which my aunt recommended and which I found at the Paris airport on our way back to New York.

In this part-memoir, part essay, part research project, the author strives to learn more about Besty, née Elizabeth, her schizophrenic and lobotomized great-grandmother. There is taboo and silence around Besty, and her treatment by her father and husband, and Adèle truly has to work to find any information about her ancestor. Like most women in her family, she is worried she might be genetically inclined to be crazy too, but the more Adèle learns, the clearer it becomes that the care and treatment Besty received was mainly responsible for her “insane” status.

There are some truly horrific moments in this novel, specifically, all of Yon’s research into the development and popularization of lobotomy in the U.S. and across Europe. The author quotes multiple medical records in which women express their despair over having received this surgery against their will. There are some very thoughtful and interesting portions on the idea that lobotomization was popularized not to cure the medically insane, but mostly to make sure women who deviated from a prescribed norm were returned to a calm and docile version of themselves, at the cost, of course, of their mental capacities, and personalities. Truly horrific stuff.

If you can speak French, I definitely recommend this book. Considering it won so many prizes in France, I wouldn’t be surprised if it got translated into English soon.